On Going Direct

Little has elicited as much discussion among my fellow communicators lately as the merits of “going direct,” or circumventing traditional media like newspapers and TV by going straight to your audience via tweets, WhatsApps, and newsletters.

My view is that the “go direct” crowd has found a real kernel of insight—that communications is fundamentally about movement-building—but that they’ve come to the wrong conclusion, overemphasizing the importance of “going direct” in your medium rather than in your message.

Going Direct

In short, this is the argument for going direct:

Once upon a time, communicators relied solely on third parties like the press to get stories into the world.

The press was a necessary evil, required for distribution but ultimately sanding the edges off truly innovative ideas.

The internet has upended the need for such intermediaries, allowing you to reach your core audiences with the precision of a laser beam, avoiding the wider blast radius of traditional media.

Ergo, companies and individuals should go direct in their messages.

Useful Fictions

The go direct crowd is right that the communications landscape is changing. Newspapers are shuttering at an alarming rate at the same time that new online platforms proliferate, creating a supernova of content for readers to shift through. In other words, there is more content and are fewer gatekeepers than just a few decades ago.

But advocates of going direct take their claim too far in both directions: Traditional media is not gasping its last breath, nor is “going direct” as precise a tool as they’d like.

Traditional Media

The “go direct” crowd will tell you that once upon a time there existed a world where communications relied solely on intermediaries like the press. Our job was simply to fax out a press release, land a New York Times story, and call it a day. Now newspapers are dying, they say, and those that are left are interested only in printing bland, uninteresting corporate drivel.

This is a useful fiction, no different than the idea that there was a lawless state of nature before there was government. Newspapers are shrinking, but news is not; media is simply evolving its form. Where there were major broadsheets and a few TV networks, now there are podcasts, niche industry outlets like The Information, locals like Axios Charlotte, newsletters like Morning Brew and The Free Press.

This means media is hardly the blunt, “be all things to all people” tool it’s been painted as. Outlets have distinct audiences: TechCrunch reaches early-stage startup geeks, Politico policy wonks, The Ankler Hollywood geeks. Even the major broadsheets have their own identities: The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg are geared toward financial types, while The Washington Post hits politicos.

Nor is traditional media beholden to corporate-speak. In fact, I know of no better way to ensure an announcement does not make news than to translate it into press-release gobbledegook. Journalists hate press releases. The perspectives that make news are contrarian and spiky, presented in plain English.

Going Direct

If traditional media can be more targeted and more interested in unorthodox opinions than the going direct crowd argues, so too is “going direct” less targeted.

Going direct typically means engaging on social media platforms where people can opt-in to follow you, like Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube. But these platforms don’t only reach those who’ve opted-in, just as news outlets don’t only reach subscribers. Platforms surface content to those they think will be interested in a given subject—not just because the viewers agree with the content, but often because they are likely to disagree. And some content is surfaced just because it’s popular with other people, regardless of whether it’s likely to be interesting to the individual.

This all means that “going direct” is not a laser beam. Social media, like its traditional counterpart, is a sort-of precise, sort-blunt tool. Even if you use an email list or a WhatsApp group—groups that are theoretically extremely tailored to their intended audience—you’re likely to hit some people with whom your message doesn’t resonate. (Anyone who’s ever expressed a sliver of interest in politics and then been unable to unsubscribe from the avalanche of emails and texts that follow has felt this viscerally.)

Going direct also doesn’t allow you to circumvent the challenge of coming up with an interesting point of view. Algorithms bury uninteresting content. The way to “win” the algorithm is more or less the way to “win” traditional media: say something that people are actually interested in hearing, which is often counterintuitive or counter-consensus in some way.

A Virtuous Cycle

My argument is not that traditional media is the be-all-and-end-all of comms, nor that going direct is foolish, but that any good comms strategy will leverage both. Going direct and traditional media create a virtuous cycle. Wherever you start, the game is to trade up over time, like the man who traded a red paperclip until he got a house.

After all, many of those who now lean heavily on “going direct” initially built their names in the major broadsheets and on broadcast networks. There is no Donald Trump without The Apprentice. For that matter, there is no Donald Trump without wall-to-wall press coverage in 2016.

Others who couldn’t garner media interest started by building up organic excitement in small communities, which in turn made them a better subject for a traditional media story…which boosted their audience and increased the size of their community, giving them more people to “go direct” to. (Red Paperclip Man is a quintessential example: He recounted his journey on a blog, which then got picked up in the news media, causing more people to follow along with his blog, and so on.)

Community-Building

So what, then, does the “go direct” contingent get right? In their emphasis on speaking only to core audiences, they correctly identify the goal of communications: rallying your base into a movement. Put another way, they get right that communications is community-building.

They’re just wrong about how to build it.

There is no world where you can speak only to those who wholeheartedly agree with you. No platform yet exists that can wholly hive off believers from nonbelievers. Even companies that theoretically employ only true believers often deal with leaks from within. Hell, even honest-to-god, cut-you-off-from-the-outside-world cults deal with leaks from within! “Believers” and “nonbelievers” are a moving target anyway; opinions can change over time. So you can’t point a laser beam at your audience and talk only to them.

But you can create messaging that appeals only to your audiences. And often the messaging that appeals most to your core believers will really turn off people who don’t agree with you. That’s good! Think about how powerfully pro-abortion messaging worked to bring Democrats to the polls in 2022, in no small part because of the vociferous anti-abortion messaging they were met with. Whatever your beliefs, “us versus them” is perhaps the world’s oldest and most effective organizing strategy.

How to Build a Movement

So how do you actually build a movement? You need to think through:

1. Who are your core audiences?

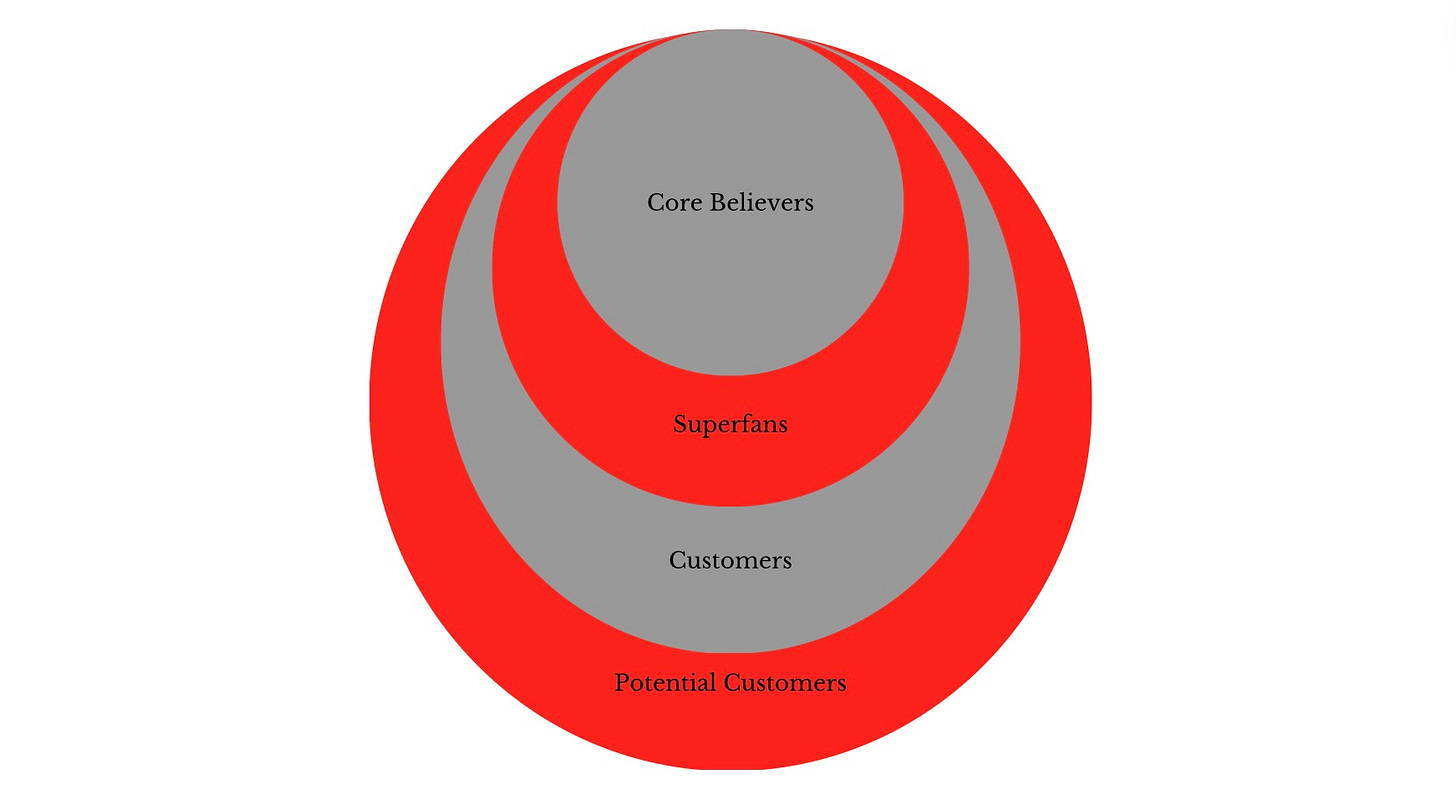

Communicators sometimes talk about a communications cascade, whereby information flows top-down. I prefer to think about audiences as a series of concentric circles, starting with your core believers and expanding outward.

Here’s a hypothetical example that would apply to most B2B and B2C companies:1

2. What do you need your audiences to believe?

Different circles need to believe different things. Core believers, which might consist of board members, executives, and superstar employees, need to believe you’re building a pathbreaking company that will meaningfully change the world. Otherwise, why would they work for you instead of a brand name like Google or Meta?

Superfans might be your top X% of customers. They are evangelicals for your product, willing to sing its praises in testimonials and ads.

Run-of-the-mill customers and potential customers, on the other hand, might only need to believe that you’re going to make a specific task two or three times easier than whatever they’re doing now. They don’t need to be bought in the same way as the inner circles, but you still need them generally on board with the mission (and also not scared off by bad press).

3. How can you most effectively reach your audiences?

Now try to figure out how to reach your audiences. This might be through traditional media or by going direct. For your innermost circles, it might even be one-on-one conversations or intimate Signal chats.2

Most likely, you’ll need to leverage multiple strategies. A story in the Times might earn you third-party legitimacy with investors, while a Facebook ad campaign might help you reach potential customers at the point of purchase.

Notice that “the press” and “Twitter” don’t get circles. That’s because they’re not audiences; they’re intermediaries. Means, not ends. You need to go through them to get your message into the world. Like all intermediaries, they have pros and cons. Choose wisely.

(Note that I’m not saying the medium doesn’t matter at all. It does! The go direct crowd is right about that. I just don’t think most mediums are so precise as to reach only your targeted audience and no one else.)

Align Medium and Message

Some companies have taken “go direct” or “build community” too literally, without thinking through these steps. For example, last year Louis Vuitton launched a Discord that seems to mostly consist of the LV social team screaming into the void. The reason forced “communities” like these don’t work is that there’s not alignment between the medium and the message. Discord doesn’t communicate luxury.

Similarly, I don’t want the CEO of my fiat bank to spend a lot of time engaging in Twitter fights (because I want her to convey “stability”), whereas I’m happy to let the founder-CEO of my crypto bank be a bit of a reply guy (because he’s disrupting an industry).

Ultimately, the game is to align your audiences, your message, and your medium. But it is a fiction to believe that you can precisely target your core believers in your medium, which even in this era of endless platforms is at best a crude instrument. The way to build community is instead through precision in your messaging.

Shoutout to former Palantir comms guru Bonnie Tom for this framework.

This framework, by the way, is why I find it silly to draw too firm a line between internal and external comms. Your employees read the news, while ostensibly “external” audiences of core believers might be best engaged via a usually internal-facing platform like Slack. They’re all just audiences to be communicated to.

Great piece!